Patents, prices, and use of essential medicines in developing countries

From the 12 million people coping with Aids/Helps with developing countries who’ll die within three years without access immediately to affordable antiretroviral medicines, only 4 million were undergoing treatment in the finish of 2008. Use of a much wider listing of essential medicines (individuals understood to be required for health by national governments or even the World Health Organization, or WHO) is every bit dismal. Recent WHO studies discovered that public pharmacies in developing countries had just one-third of essential medicines available onsite, and also the private pharmacies had 3-thirds of medicines available. Finish prices were 2.5 and 6.5 occasions worldwide reference prices at private and public pharmacies, correspondingly [1]. As poor as accessibility to essential medicines is, use of newer medicines, including individuals for chronic illnesses, is a whole lot worse, since these patent-protected medicines are extremely costly to become incorporated on essential medicine lists. Finally, there’s been so very little development and research into neglected illnesses affecting mainly the indegent in poor countries that treatments don’t even exists for these conditions [2].

Many factors lead to too little use of existing medicines in developing countries: tattered health systems, inadequate figures of health workers, weak regulatory regimes, and poor procurement and distribution systems. Other conditions—import responsibilities and taxes, mark-ups through the distribution chain, as well as corruption and product diversion—coalesce to create high drug prices. Weak development and research (R&D) capacity and limited purchase of R&D combine to limit research on neglected illnesses in developing countries. But clearly among the factors most implicated in unavailability (and unaffordability) of medicines in developing countries may be the current ip regime—a regime that enables proprietary drug companies with ip monopolies to charge high costs and maximize gain the purchase of medicines that just wealthy and well-insured people are able to afford while concurrently deprioritizing R&D into items that the indegent need.

The unconscionable gap in use of existence-saving and existence-enhancing medicines reflects an enormous disconnect between, around the one hands, the perceived interests of wealthy countries within the global North and also the proprietary pharmaceutical firms that research, develop, and convey patented medicines and, however, the interests of developing countries within the global South. This disconnect occurs in the intersection of two separate systems: national and worldwide ip regimes, and global patterns of poverty and earnings inequality.

From the 12 million people coping with Aids/Helps with developing countries who’ll die within three years without access immediately to affordable antiretroviral medicines, only 4 million were undergoing treatment in the finish of 2008. Use of a much wider listing of essential medicines (individuals understood to be required for health by national governments or even the World Health Organization, or WHO) is every bit dismal. Recent WHO studies discovered that public pharmacies in developing countries had just one-third of essential medicines available onsite, and also the private pharmacies had 3-thirds of medicines available. Finish prices were 2.5 and 6.5 occasions worldwide reference prices at private and public pharmacies, correspondingly [1]. As poor as accessibility to essential medicines is, use of newer medicines, including individuals for chronic illnesses, is a whole lot worse, since these patent-protected medicines are extremely costly to become incorporated on essential medicine lists. Finally, there’s been so very little development and research into neglected illnesses affecting mainly the indegent in poor countries that treatments don’t even exists for these conditions [2].

Many factors lead to too little use of existing medicines in developing countries: tattered health systems, inadequate figures of health workers, weak regulatory regimes, and poor procurement and distribution systems. Other conditions—import responsibilities and taxes, mark-ups through the distribution chain, as well as corruption and product diversion—coalesce to create high drug prices. Weak development and research (R&D) capacity and limited purchase of R&D combine to limit research on neglected illnesses in developing countries. But clearly among the factors most implicated in unavailability (and unaffordability) of medicines in developing countries may be the current ip regime—a regime that enables proprietary drug companies with ip monopolies to charge high costs and maximize gain the purchase of medicines that just wealthy and well-insured people are able to afford while concurrently deprioritizing R&D into items that the indegent need.

The unconscionable gap in use of existence-saving and existence-enhancing medicines reflects an enormous disconnect between, around the one hands, the perceived interests of wealthy countries within the global North and also the proprietary pharmaceutical firms that research, develop, and convey patented medicines and, however, the interests of developing countries within the global South. This disconnect occurs in the intersection of two separate systems: national and worldwide ip regimes, and global patterns of poverty and earnings inequality.

When it comes to trade policy, the U.S. government has consistently supported the commercial interests from the highly lucrative U.S. pharmaceutical industry at the fee for use of less expensive medicines in developing countries [3]. The best illustration of this feeling of priorities happened in multilateral negotiations that established a uniform system of worldwide ip legal rights in 1994: the WHO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Facets of Ip Legal rights (Journeys) [4].

The Journeys agreement introduced minimum global standards for safeguarding and enforcing almost all types of ip legal rights (IP), patents, copyrights, and trade secrets, including individuals signing up to pharmaceuticals. It covers fundamental concepts, standards and employ of patents, IP enforcement, dispute settlement, along with other subjects. Under its key provisions, WTO states must provide patent protection for at least twenty years in the filing date of the patent application for just about any invention, together with a pharmaceutical product or process, that fulfills the factors of novelty, invention, and effectiveness.

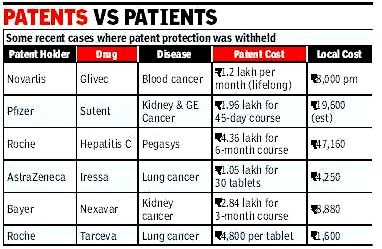

Preceding patent-rule pluralism both in the developed and third world had permitted discrimination between fields of invention, for instance by excluding medicines, but Journeys specifically outlawed such discrimination. Similarly, it had been no more allowable to discriminate against imports in support of local products, thus allowing major pharmaceutical companies to manage the place of production. Due to Journeys, the main pharmaceutical producers been successful in consolidating their monopoly power internationally—they have exclusive legal rights under Journeys to exclude others from “making, using, offering for purchase, selling, or importing” patented pharmaceutical products or “products created using a patented process” [4]. Whenever a patent holder can exclude others, it frequently charges monopoly prices, and it is profit-maximizing strategy in developing countries is usually to market medicines at high costs towards the wealthy even when that cost excludes purchase by or most a country’s population.

Despite its many patent protections for drug companies, the Journeys agreement also outlined some key flexibilities open to countries to guard public health insurance and use of medicines. Countries were allowed to consider stringent standards for patentability pursuant to their personal legislation these were permitted to issue compulsory licenses that permitted others to fabricate then sell the patented medicine as long as a royalty was compensated towards the patent holder and certain procedures were adopted these were permitted to make use of parallel importation to shop around for any brand-name medicine whether it was offered elsewhere in a lower cost plus they received transition periods within which to get Journeys-compliant.

Despite securing baseline ip protections in Journeys, the U . s . States ongoing huge-handed trade policy that threatened developing countries for example Thailand, Nigeria, and South america with trade sanctions simply because they declined to allow increased Journeys-plus legal rights to patent holders or suggested using Journeys-compliant way to access less expensive medicines [5]. These threats (e.g., withdrawal of special zero-tariff trade access or of U.S. foreign investment) ongoing even in the end WTO people such as the U . s . States signed the Doha Declaration around the Journeys Agreement and Public Health, which clarified developing countries’ leeway to issue compulsory licenses and also to otherwise ensure use of medicines for those [6].

Within the publish-Doha era, the U . s . States is constantly on the penalize and threaten countries that resist greater ip standards or which use Journeys-compliant flexibilities. Furthermore, despite trade authorization legislation on the contrary, the U.S. trade representative is constantly on the seek enhanced, Journeys-plus ip protections in bilateral and regional trade negotiations [7]. The Democratic Congress finally enforced limited controls around the U.S. trade representative regarding health-affecting ip provisions of 2007, but the Federal government seems to become going after old-school, intellectual-property-legal rights maximization strategies as evidenced by its recent report listing countries that don’t provide U.S.-level ip protections [8, 9].

Neo-liberal economic theory promotes strong that has been enhanced ip legal rights, including individuals of pharmaceutical producers, because the magical path to development, believing the rising tide of import-export economies can help fund rehabilitation of unsuccessful public health sectors, which ip protections will promote local development and research of medicines for indigenous illnesses present in Africa, South America, and Asia. This theory offers little solace for millions of people coping with health problems which will kill them prematurely or undermine their quality of existence. A far more practical solution, presently went after by health activists worldwide, may be the promotion of robust generic pharmaceutical production, operating at efficient economies-of-scale to ensure that medicines can be created offered at the cheapest possible cost. To create these drugs open to all, activists have been successful in creating funding structures like the Global Fund to battle AIDS, T . b, and Malaria and also the U.S. President’s Emergency Arrange for AIDS Relief, as well as in agitating for greatly enhanced bilateral and multilateral donations so there are reliable and sustainable reservoirs of buying capacity to support an industry in generic pharmaceuticals and finance acquisition of vast amounts of drugs.

Paradoxically, activists have switched towards the sell to solve the marketplace failure they’ve resorted to promoting free competition and warranted purchasing power as tools of preference for making access a real possibility. But individuals tools are only able to be actualized by reforming worldwide trade contracts and national patent schemes to facilitate global commerce in high-quality, low-cost generic medicines. As evidence of concept, activists can indicate what is happening towards the prices of AIDS medicines, a plummet in cost from greater than $10,000 per patient each year in 2000, to simply $87 per patient each year 8 years later [10].

Simultaneously they have switched pragmatically towards the market, activists have recommended for any more benign type of globalization, for multilateral unity structures, like the Global Fund, to coordinate the worldwide reaction to pandemic disease. Activists have humanized their “free generic trade” and “multilateralist” rhetoric, however, having a call to human rights—a demand the immediate, or at best expedited use of health care and cost-effective medicines. They’ve done this forcefully, even theatrically with mass demonstrations, civil disobedience, and intense lobbying in its northern border and also the South. Frequently they’ve done this by concerted action, with global times of protest against drug companies, governments, and multinational corporations [11].

More lately, health activists have promoted new mechanisms to inspire generic exchange medicine and also to expand research into neglected illnesses. Probably the most promising innovations involves the development of a “patent pool” by UNITAID, the brand new worldwide drug purchasing facility, partly funded by an air travel tax under your own accord adopted by a number of countries that supports production and procurement of improved medicines for Aids/AIDS, TB, and malaria. This patent pool will initially seek under your own accord negotiated in-licenses of Aids-related patents and manufacturing know-how from Big Pharma and can then out-license legal rights to fabricate then sell to quality-assured generic producers. A unique feature of those licenses will give you incentive for growth and development of rational fixed-dose combination medicines and pediatric formulations the current system doesn’t provide [12].

Another innovative proposal promoted by Understanding Ecosystem Worldwide, Doctors Without Borders, yet others inside the WHO Global Strategy and Strategy on Public Health, Innovation, and Ip encourages research into neglected illnesses by the development of “prize funds” to reward researchers and producers for developing medicines which have a substantial therapeutic effect on heretofore neglected tropical illnesses [13]. Although advance purchase commitments, private and public partnerships, and research grants are also mechanisms for supporting focused research on tropical illnesses, the prize fund proposal holds special promise since it basically separates the marketplace for innovation from the marketplace for low-cost production and purchase. A prize fund rewards inventors who produce needed, therapeutically significant innovations in research platforms, products, and procedures. The innovation should be a “public good,” allowing production and purchase by multiple generic producers.

The rebuff of patents, ascendancy of exchange generics, and the authority to treatment all demonstrate the outcome that coordinated global movements might have around the renovation of public imagination, social institutions, and legal plans. Through this renovation, we’ve altered from the world that thought management of people coping with Aids/Helps with developing countries was impossible, (or perhaps in the language around the globe Bank, “not economically efficient”) to some world where use of antiretroviral therapy has elevated with a factor of 10 in only five years. One at a time, activists have attacked structural and legal barriers to gain access to, such as the worldwide ip regime, and also have imagined after which recommended for brand new institutional plans and policies that may make treatment a real possibility.

The access that individuals coping with Aids/AIDS have started to have should be extended to the indegent in developing countries more broadly. We have to develop an expanded campaign, one which deploys conflicting discourses—competition, public health, antiglobalization, and human rights—in quest for a precondition where all human development depends: a population healthy enough to outlive past mid-life. In connection with this, health activists’ amalgamated right-to-treatment discourse is among community as well as positive and equitable legal rights, by which the truly amazing global imbalance in use of medicines is susceptible to radical redistribution, North to South, wealthy to poor, white-colored to black, male to female, and adult to child.

Resourse: https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/patents–prices-and-access-essential-medicines-developing-countries/